1 in 6 Chicago third graders can read at level, signaling dismal futures

Few Chicago third-grade students can read at grade level. Even fewer low income and minority students are at grade level in reading. Research shows this is a warning sign for Chicago students’ academic success and subsequent earning potential.

About one-sixth of all third-grade students in Chicago Public Schools can read at grade level. For low-income and minority students, the share of proficient readers is even lower.

A student’s “academic success, as defined by high school graduation, can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by knowing someone’s reading skill at the end of third grade,” according to the National Research Council.

By this measure, the outlook for Chicago third-grade students is grim. Even more troubling is the outlook for Chicago students from low-income and minority families.

What’s at stake isn’t just poor grades on report cards in third grade, but what that lack of reading proficiency means for the future. Research shows the poor reading proficiency plaguing Chicago’s children threatens to condemn them to poverty later in life – and the price will be paid not just by them, but by society at large.

Third-grade literacy in Chicago

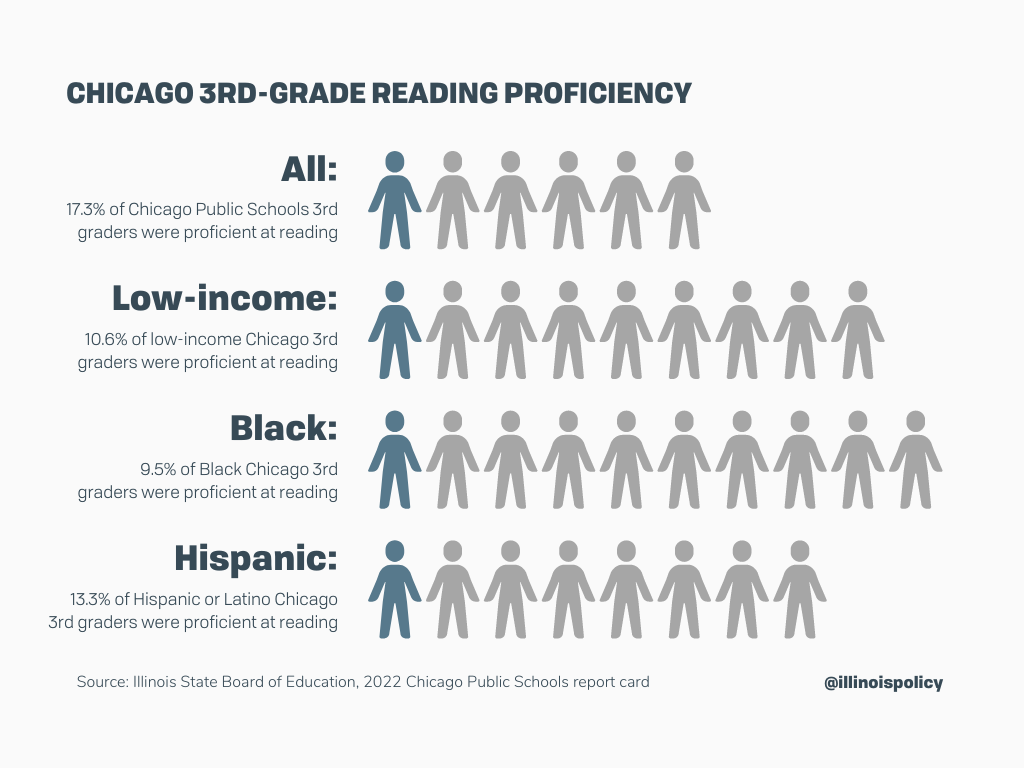

In CPS in 2022, just 17.3% of students could read at grade level by the end of third grade. Only 6% of the 457 Chicago schools for which the Illinois State Board of Education recorded proficiency rates among third graders had at least half of third grade students reading at grade level. There were 82 schools in which no third-grade students were proficient at reading.

The statistics are even worse among low-income students.

Just 10.6% of low-income third-grade students in Chicago were reading at proficiency. In 91 schools, not a single low-income, third-grade student could read at grade level. Only six schools had at least half of the low-income third grade students reading at grade level.

Minority students are likewise struggling to read at grade level in CPS. Just 9.5% of Black third-grade students could read at grade level in 2022. In 30% of the 253 schools with proficiency for Black third-grade students, no Black third-grade students could read at grade level.

Districtwide, just 13.3% of Hispanic or Latino third-grade students could read at grade level. In 24 of the 221 schools with data, no Hispanic or Latino third graders could read at grade level in 2022, and only 12 schools had at least half reading at grade level.

Third grade literacy as a predictor of academic success

A report by the Annie E. Casey Foundation warns about the negative effects of a student’s inability to read effectively by the end of third grade.

The research shows a student’s likelihood to graduate high school can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by their reading skill at the end of third grade. By the beginning of fourth grade, students transition from learning to read to reading to learn. According to the Children’s Reading Foundation, if a student struggles to read at grade level by this critical point, up to half of the printed fourth-grade curriculum is incomprehensible.

The authors warn that “if we don’t get dramatically more children on track as proficient readers, the United States will lose a growing and essential proportion of its human capital to poverty, and the price will be paid not only by individual children and families, but by this entire country.”

The price paid by the individual for poor third-grade literacy is lower earning potential. The median annual earnings of adults ages 25 through 34 who had not completed high school were lower than the earnings of those with higher levels of educational attainment, according to data from the Census Bureau’s 2017 Current Population Survey,.

The unemployment rate for high school dropouts was 13% compared to the 7% unemployment rate of those whose highest level of educational was a high school credential.

Society also pays a price for failing to prepare its students to read at grade level by the end of third grade. The National Center for Education Statistics reported during his or her lifetime, the average high school dropout cost the economy approximately $272,000 compared to individuals who complete high school because of “lower tax contributions, higher reliance on Medicaid and Medicare, higher rates of criminal activity, and higher reliance on welfare.”

It’s time Illinoisans took note of the poor proficiency rates plaguing the state’s schoolchildren. There is more at stake than bad grades for young Illinoisans who are struggling to learn vital literacy skills in their early school years. Elementary Illinois students need intervention now before their lack of childhood learning becomes a barrier to a high school diploma and higher earning potential, and a slide into poverty.