The problem

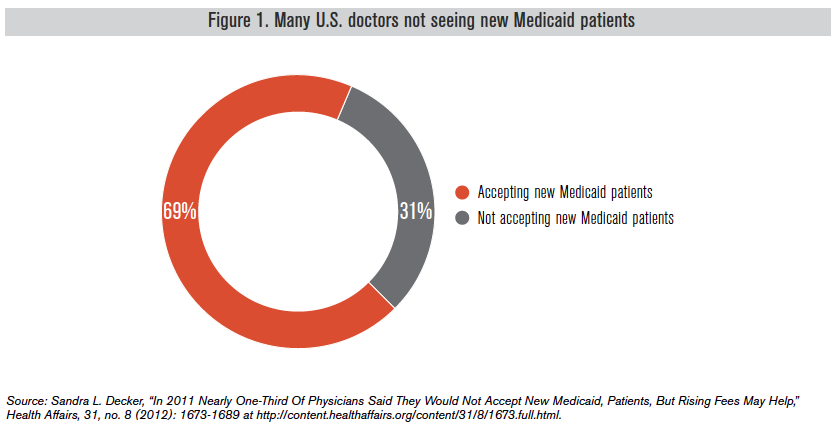

When the Affordable Care Act, otherwise known as ACA or ObamaCare, was first implemented, more than three out of 10 physicians across the country were not accepting new patients in Medicaid, a joint state-federal program that is meant to cover the costs of providing health care to the poor.

But rather than offering wholesale reform to address Medicaid’s sub-par patient outcomes, limited access to physicians and skyrocketing program costs, the ACA introduced extra incentives for states to further expand the program. At present, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded their Medicaid programs. Five more are pursuing expansion or have expressed an interest in it.

To entice more physicians to participate in the program, the ACA includes higher reimbursements for some of primary care physicians’ routine services. This payment boost applies only to a select group of primary care and family medicine physicians (and excludes OB-GYNs, for example) and is only available for 2013 and 2014. Preliminary anecdotal data indicate that there has not been a significant increase in physician participation, and physician shortages in medical specialty areas continues to worsen under the Medicaid program.

Not only will these Medicaid expansion efforts likely exacerbate patients’ ability to access quality care, but the problem of finding a physician willing to take new Medicaid patients is also about to become worse.

Background

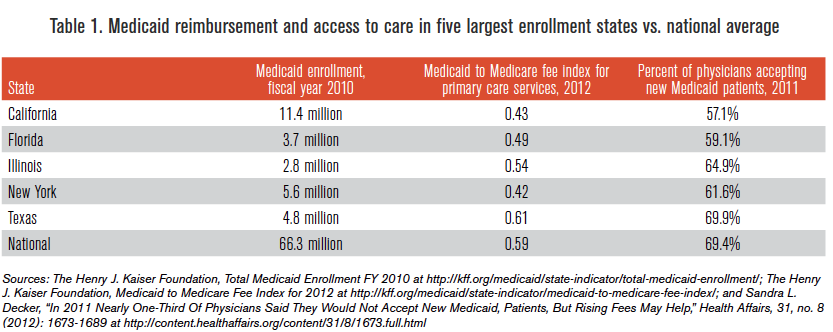

Even though a patient is “insured” under the Medicaid program, patients routinely face barriers to accessing care. In many states, the program often pays physicians 59 percent of what Medicare pays for primary care services – which is even lower than what private insurance pays.1

In fact, the five states with the largest Medicaid enrollments, accounting for more than 40 percent of the total national Medicaid enrollment when ObamaCare was enacted, were all well below the national average in physician primary care reimbursements2 (see Table 1). Not surprisingly, four out of five of these states were well below the national average with regard to the percent of physicians accepting new Medicaid patients.

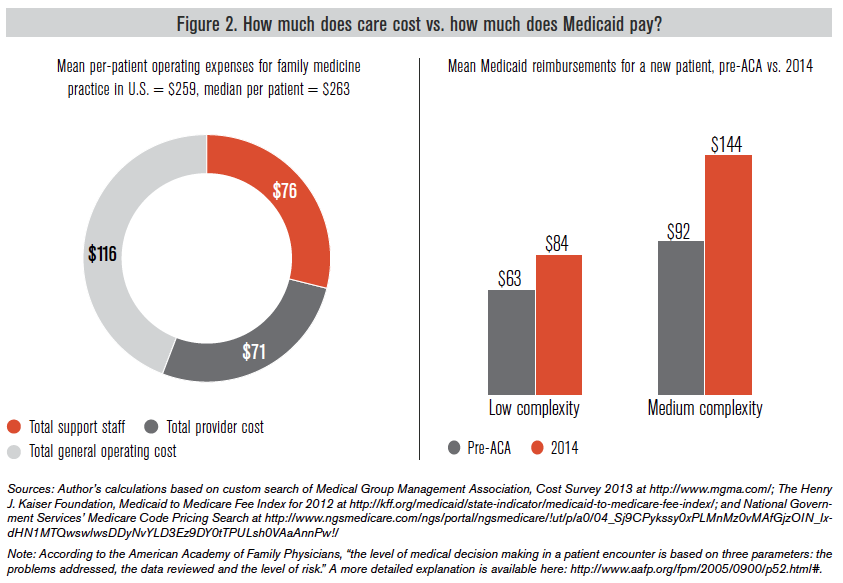

In an effort to rein in program costs, state lawmakers too often default to cutting provider reimbursements. In 2011 alone, 15 states imposed provider payment reductions in an effort to respond to state budget pressures, and almost half of those states made similar cuts in the prior year.3 In fact, Medicaid reimbursements are often below the actual cost of treatment (see Figure 2).

While Medicaid payments for some primary care services provided by primary care and family medicine physicians will be paid on par with what Medicare pays for 2013 and 2014, the higher reimbursements are scheduled to revert back to 2012 Medicaid reimbursement levels. But even these temporary, higher levels are often below the physician’s actual cost of providing that care.

That explains, in large part, why many physicians no longer take new Medicaid patients. In an effort to boost physician participation in the Medicaid program, reimbursements for some primary care services have been increased to Medicare levels for 2013 and 2014.4 These rates apply to Medicaid in both ACA expansion and non expansion states.

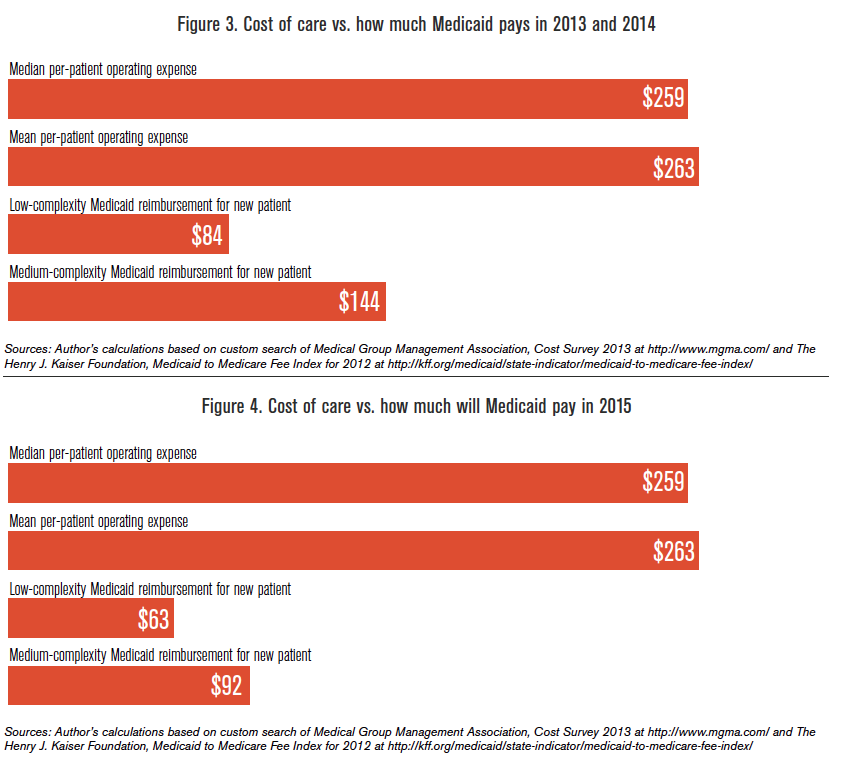

But these increases are only temporary and will expire at the end of the year. And while the reimbursements vary from state to state, the higher reimbursement rates are often still below the actual cost of care (see Figure 3).

While data on whether the reimbursement boost enticed primary care physicians to accept new Medicaid patients is not yet available, early indications from 15 major cities across the country show that Medicaid acceptance rates for primary care physicians increased in only six of 15 cities between 2009 and 2013.5 Of all physician specialties, fewer than 46 percent were accepting Medicaid patients in these 15 cities in 2013 compared to 55 percent in 2009.6

Since the higher rates were only authorized for two years, many physicians might have been reluctant to accept new Medicaid patients knowing that they would likely, once again, face pre-ACA reimbursement rates. Unless the states are willing to foot the bill for their share of the $11 billion tab to keep the higher reimbursement levels, or the federal government makes the increased rate permanent, Medicaid reimbursements will automatically revert back to the pre-ACA levels in 2015 (see Figure 4).

Conclusion

It is time to provide our state’s most vulnerable populations with true access to needed care. The guiding principle of reforming the outdated and inefficient Medicaid program should be: How can states best serve both the most vulnerable populations and taxpayers, while giving Medicaid patients more control over their own health care?

The temporary provider-payment increases for Medicaid primary care services will soon expire. Lawmakers’ default approach of curtailing Medicaid spending has resulted in barriers to care. This approach has not only undermined access for patients, but it also poses a moral problem where patients have been granted coverage without an adequate infrastructure to actually provide care.

Temporarily boosting a narrow subset of physicians’ reimbursements to entice greater participation in the Medicaid program is a gimmick. Preliminary anecdotal data indicates that this temporary boost has not increased primary care physician participation and that physician shortages in medical specialty areas are continuing to get worse under the Medicaid program.

Not only will this “doctor fix” fail to provide true access to those already in the program, but it is yet another example of why Medicaid’s command-and-control approach to health care routinely fails to deliver quality care to patients and is fiscally unsustainable.

Approaches such as sliding-scale premium assistance, where nonelderly and nondisabled patients can purchase health insurance based on price to best meet their own individual needs and preferences, as well as control their health savings account, should be explored. Those who were willing and able could also supplement their coverage plans using their own resources.

Rather than focus on patient-centered reforms that would deliver high-quality care to the neediest among us, the Obama administration continues to double-down on the bureaucratic and expensive Medicaid program. At a minimum, lawmakers should be willing to demonstrate how they are going to provide access to care – and not merely dole out Medicaid cards to patients.