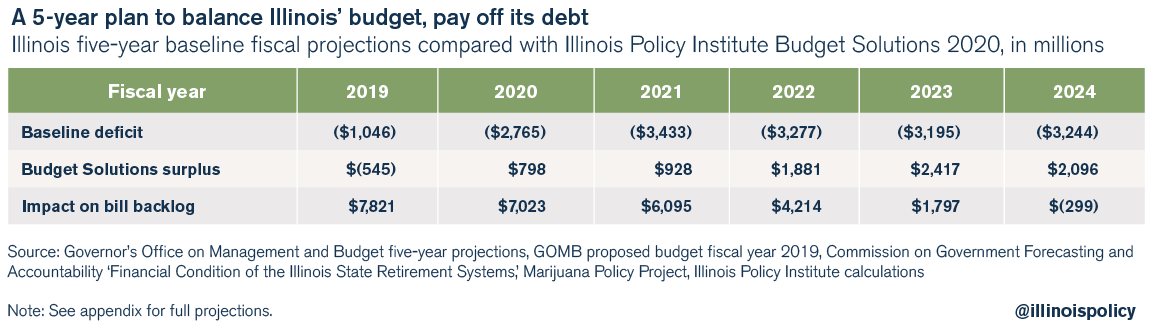

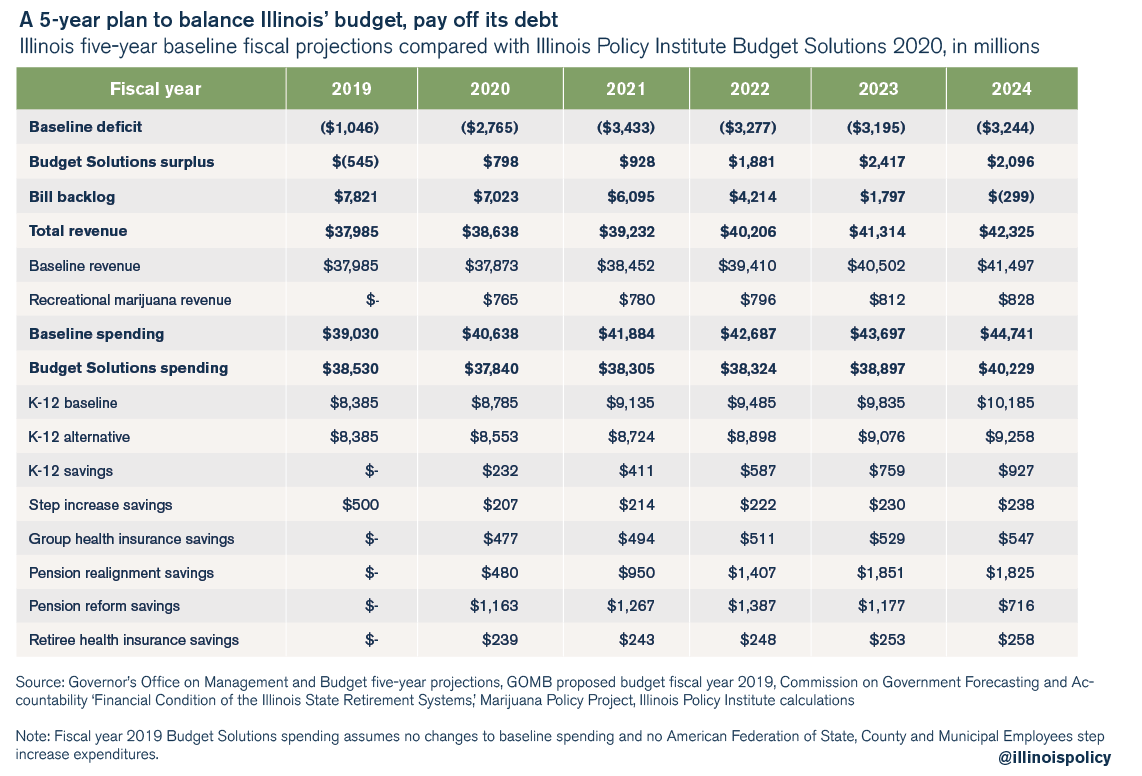

Gov. J.B. Pritzker inherited a $2.8 billion budget deficit the moment he stepped into office. Next year, that deficit is projected to be $3.4 billion1.

It’s the same story every budget season. But Illinois’ budget crises could be a thing of the past if the state would adopt pension reform, right-size its union contracts and focus education spending on classrooms instead of on administrative bloat.

Addressing these main cost drivers now could turn the state’s perpetual deficits into surpluses in just five years, creating the opportunity to pay off debt, cut taxes and stimulate economic growth.

In fact, if this plan had been implemented four years ago, in fiscal year 2016, it might have protected taxpayers and services from the budget impasse. Over four years, these structural spending reforms would have saved a total of $12.6 billion. The bill backlog would be $4 billion lower than it is today, which would have made it possible to pay off Illinois’ bills entirely next year and cut the income tax the year after that without adding to the deficit.

In his first budget address, Pritzker has the chance to make structural spending reforms that will balance the state budget and put Illinois on a path toward completely eliminating its debt. With these structural spending changes, Illinois lawmakers could join the rescue and provide a deficit-neutral tax cut as early as fiscal year 2024, or use surpluses to shore up the state’s rainy day fund.

In other words, Illinois’ elected leaders can set themselves apart from decades of failed political leadership by stepping up to take heroic action. They can be the champions who save Illinois, and do it in five years.

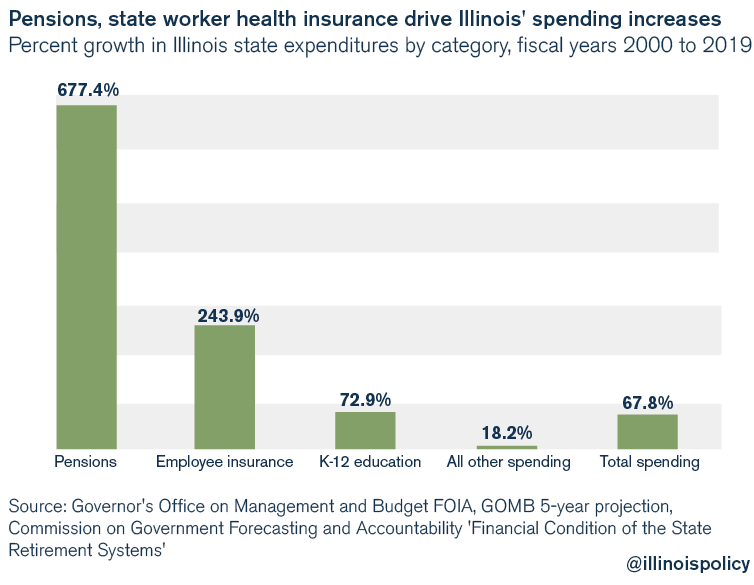

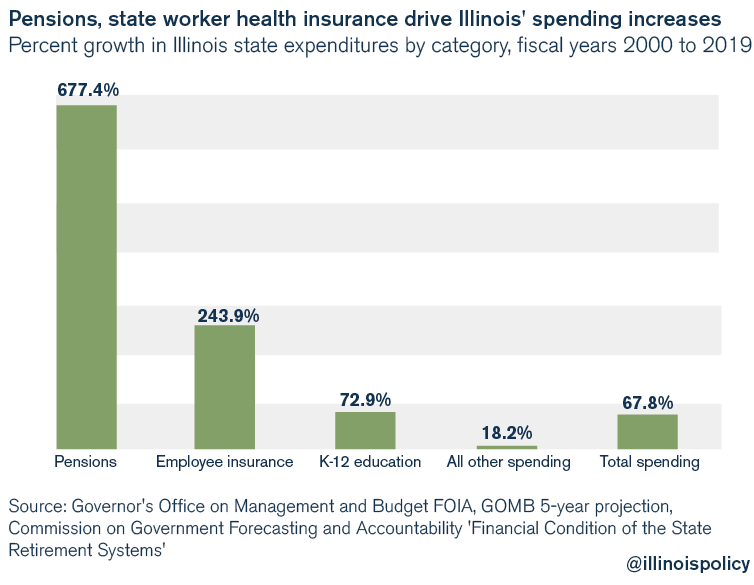

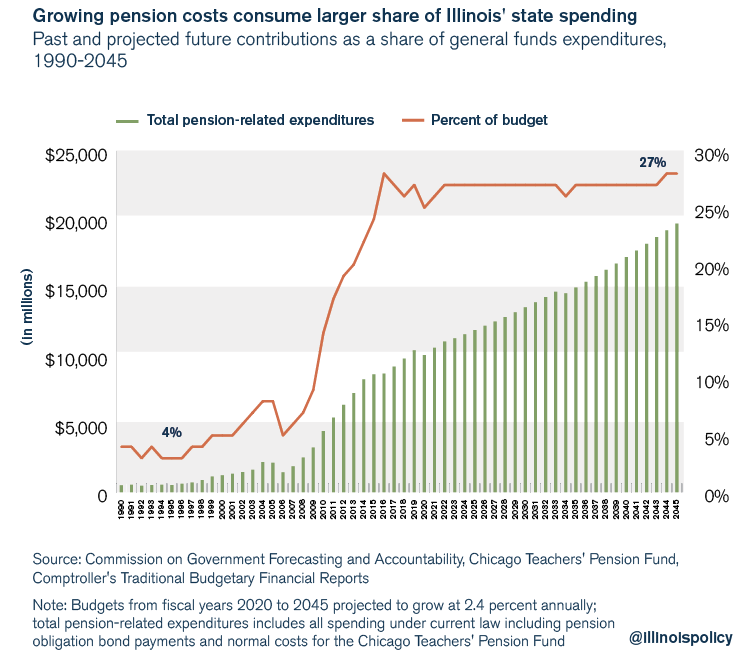

To effectively confront Illinois’ fiscal crisis, Pritzker must address the cost drivers of Illinois’ budget problems. A clear-eyed analysis of the math reveals which programs are driving overspending in Illinois. Since fiscal year 2000, state spending on pensions has grown more than 677 percent while total state spending has risen by 68 percent.

Pensions and government worker health insurance are growing faster than everything else, preventing the state from making investments in programs residents value, such as higher education, K-12 education, mental health services, the social safety net and more.

By embracing commonsense solutions, many of which have drawn bipartisan support in the past and could again, Pritzker and state leaders can accomplish what pessimistic Illinoisans might have thought impossible. The solutions are as follows:

1. Real, lasting pension reform: Savings of $12.2 billion over five years

a. Amend the state constitution so that it still protects earned benefits, but allows changes in future benefit accruals. Then, reintroduce reforms similar to those passed through the Democratic supermajority-controlled General Assembly and signed by a Democratic governor in 2013.

b. Align responsibility for setting benefits with accountability for paying benefits at schools and universities.

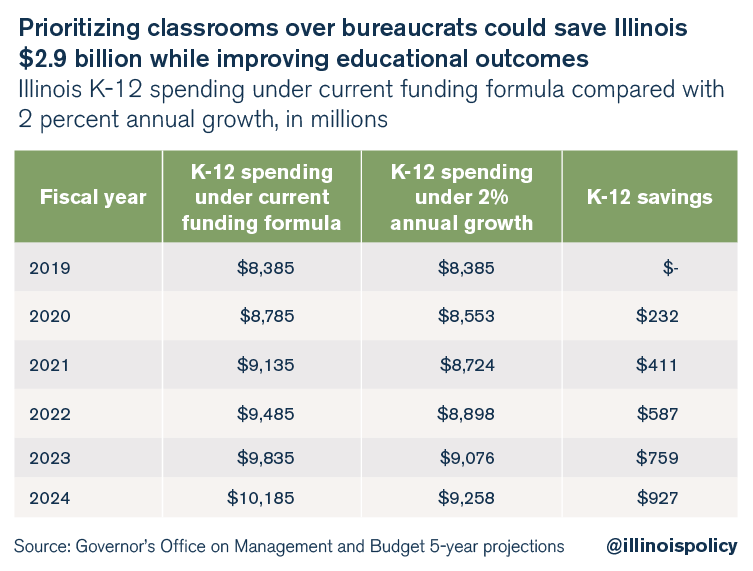

2. Invest in classrooms over bureaucracy: Savings of $2.9 billion over five years

a. Invest more money in classrooms, students and teachers by reducing administrative bloat through school district consolidation.

b. Increase education funding to keep pace with inflation rather than the $350 million annual increases envisioned in the state’s new “evidence-based” education funding formula.

3. Ask government unions to play fair at the bargaining table: Savings of $4.2 billion over five years

a. Limit automatic pay raises for some of the nation’s highest-paid state workers

b. Right-size group health insurance costs while maintaining quality care

Introduction

Illinois has achieved national notoriety for its decades of fiscal mismanagement and bad budgeting. The Mercatus Center at George Mason University recently released a report finding Illinois’ fiscal health to be the worst in the nation.2

The state’s 736-day budget impasse made national headlines and set a record for the longest a state has ever gone without passing a budget.3 For fiscal years 2016 and 2017, the state never enacted a full-year comprehensive budget. During this budget impasse, Illinois’ already worst-in-the-nation credit rating dropped even farther.4 Recently, S&P Global Ratings blamed the state’s “persistent crisis-like budget environment” for rating Illinois bonds just one notch above junk.5

The fiscal and economic problems plaguing the Prairie State are numerous and have built up over decades from bad public policy. The largest single contributing factor to Illinois’ problems, though, is a broken pension system and massive unfunded liability that recently set a record for the highest pension debt-to-revenue ratio on record for any U.S. state, at 601 percent.6

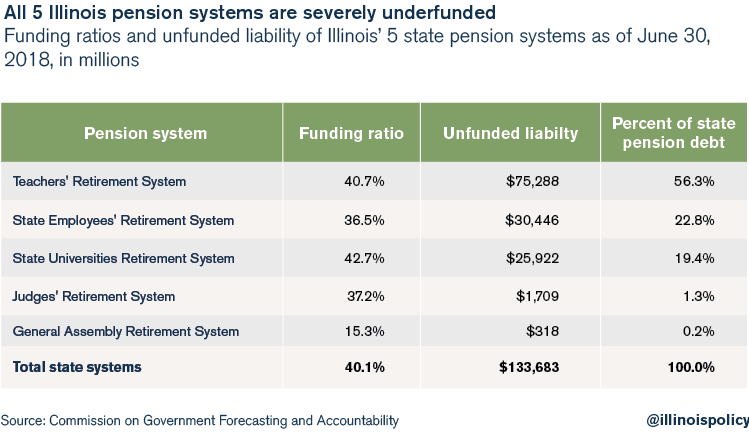

A variety of factors contribute to Illinois’ fiscal and economic problems, such as massive outmigration and crushing property taxes, but these crises can be traced back to the state’s $133 billion in unfunded pension liabilities.7 Meaningful pension reform is a necessary first step to solving other challenges facing Illinoisans.

Much like a family making a budget around their kitchen table, putting Illinois on a path to long- term fiscal health requires addressing the structural cost drivers of the state’s overspending.

The average American household spends just over 25 percent of their annual income on housing and just under 10 percent on food.8 Imagine instead a young couple spending 50 percent of their annual income on housing and 20 percent on food because they rent an apartment they cannot afford and enjoy eating out at fine restaurants multiple times each week. Their remaining income would not be enough to cover their other expenses. Over time, they would probably rack up credit card debt and would have trouble paying their bills, putting their credit health at risk.

Illinois is already there.

Now imagine that same couple trying to balance their budget and pay off their debts without reducing their spending on fine dining or looking for a more affordable home. They would be fooling themselves.

Much like a family, Illinois cannot solve budget problems when politicians refuse to clearly look at the main causes of the state’s poor fiscal health: rapidly rising costs for pensions and government worker health insurance.

According to data from the National Association of State Retirement Administrators, Illinois’ state and local governments spend nearly double the national average on pensions, measured as a percentage of all state and local spending.9 This makes Illinois government spending on pensions the highest in the nation.10

Similarly, a recent report from an analyst at J.P. Morgan found Illinois spends more than any other state on pensions, retiree health care and interest on debt, at 26 percent of revenue.11 Worse, the report found that to fully fund pensions and retiree health care at current benefit levels, the state would need to increase spending on those items to 50 percent of all revenues.12

A clear-eyed analysis of the math makes it clear which programs are driving overspending in Illinois.

Since fiscal year 2000, state spending on pensions has grown more than 677 percent, and spending on government worker health insurance has grown nearly 244 percent. Meanwhile, spending on K-12 education, often touted as a top priority by Illinois politicians, is up slightly less than 73 percent. All other spending, including social services for the disadvantaged, is up just over 18 percent. Total spending has risen by nearly 68 percent.

A clear line can be drawn between these structural cost drivers and the fact that since 2001 Illinois has not had a truly balanced budget, one in which annual revenues met or exceeded annual expenditures.

As a result of this long history of the state spending beyond its means, the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, or GOMB, predicts the state will end the year with more than $7.8 billion in unpaid bills, which come with high interest penalties that must ultimately be paid by taxpayers.13

And yet, the good news is the state’s problems are solvable if policymakers can summon the will and the courage to realistically address the current situation and pursue commonsense solutions.

A good budget for Illinois will:

- Create structural balance between revenue and expenditures in both the short run and long run

- Create short-term surpluses that can be used to pay off the state’s bill backlog

- Protect core government services such as education and social services

- Put Illinois on a path to make deposits to a rainy day reserve fund and provide tax relief to struggling residents

All of this can be accomplished in five years – by fiscal year 2024 – with spending reforms that should be embraced by lawmakers from across the political spectrum. These critical spending reforms are:

1. Real, lasting pension reform

a. Amend the state constitution so it still protects already-earned benefits, but allows changes in future benefit accruals. Then, reintroduce reforms similar to those passed through the Democratic supermajority-controlled General Assembly and signed into law by a Democratic governor in 2013.

b. Align responsibility for setting benefits with accountability for paying benefits at schools and universities.

2. Invest in classrooms over bureaucracy

a. Invest more money in classrooms, students and teachers by reducing administrative bloat through school district consolidation.

b. Increase education funding to keep pace with inflation rather than the $350 million annual increases envisioned in the state’s new “evidence-based” education funding formula.

3. Ask government unions to play fair at the bargaining table

a. Limit automatic pay raises for some of the nation’s highest-paid state workers

b. Right-size group health insurance costs while maintaining quality care

If these structural spending reforms are implemented, Illinois can eliminate its bill backlog by fiscal year 2024 and begin talking about reducing income taxes without having to cut social services, curb education or create a budget deficit.

Along with the first-year bill backlog projection, the baseline spending and revenue numbers above are from GOMB’s most recent five-year projection. The report notes that the U.S. is in the 10th year of one of the longest economic expansions in American history and that a “yield curve inversion” – when the return on investment of short-term bonds is higher than the yield on longer-term bonds – appears imminent. Both indicators seem to predict a national recession in the near term, and GOMB’s revenue forecast therefore assumes a mild recession lasting from the fourth quarter of fiscal year 2019 to the second quarter of fiscal year 2020.14

Thus, if the economy does not enter a recession, annual budget surpluses will be even higher than shown here, and tax relief can come sooner.

Marijuana revenue is included in the projections because Pritzker and Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan have both said legalizing recreational marijuana is a priority.15 Although Pritzker has said he believes recreational marijuana revenues could be as high as $1 billion annually,16 the highest estimate from the Marijuana Policy Project – assuming taxation similar to Colorado’s and to provisions in a bill introduced in the Illinois Senate in 2017 – is $700 million annually.17 Marijuana revenues are then assumed to grow at 2 percent annually, which is the long-range inflation target of the Federal Reserve and the expectation of the econometrics firm IHS Markit, used by GOMB for revenue projections.18

To achieve these budgetary savings and improve Illinois’ foundational budget-making procedures, Pritzker must realistically assess the state budget and break with Illinois’ status quo of deferring payment and kowtowing to special interest groups.

Real, lasting pension reform: $12.2 billion over 5 years

The most critical single aspect of any good budget plan in Illinois is meaningful pension reform to put the state on a trajectory where pension contributions are significantly lower in the short term but also sufficient to eliminate the state’s unfunded liability more quickly than planned under current law.

The state has at least $133 billion in pension debt across the five state systems, which doesn’t even include local government pension debt.

Pensions as a share of the general revenue budget have been dramatically increasing for decades and will continue to take up more than a quarter of the state budget even if the state’s optimistic assumptions – such as high investment returns and low growth in salaries and life expectancy – hold true.

Due to a 2015 Illinois Supreme Court decision declaring unchangeable all past and future pension benefits under the contract in effect at the start of a worker’s employment, the only realistic path forward on pension reform starts with a constitutional amendment.19

A constitutional amendment must be approved by three-fifths majorities of both houses of the Illinois General Assembly and then be approved by voters in the next general election in November 2020. The governor does not need to sign resolutions for constitutional amendments,20 but Pritzker’s support for such an amendment could be critical in getting the legislature to act.

Fortunately, the General Assembly does not need to wait until a pension amendment is approved by voters to start saving taxpayers money.

Constitutional amendment: protecting both taxpayers and retirees

Changes to slow the growth in future pension benefits require a constitutional amendment. However, the General Assembly maintains the legal authority to reduce annual contributions to the pension system and has done so in the past. In other words, state lawmakers could pass a budget that funds the pension systems at levels sufficient to reach full funding under the system that would be put in place following a successful amendment.

Pursuing pension savings in this way would allow immediate savings and also inform future voters about the consequences of approving, or not approving, a constitutional amendment. This would help voters make an informed choice and make passage of the amendment more likely.

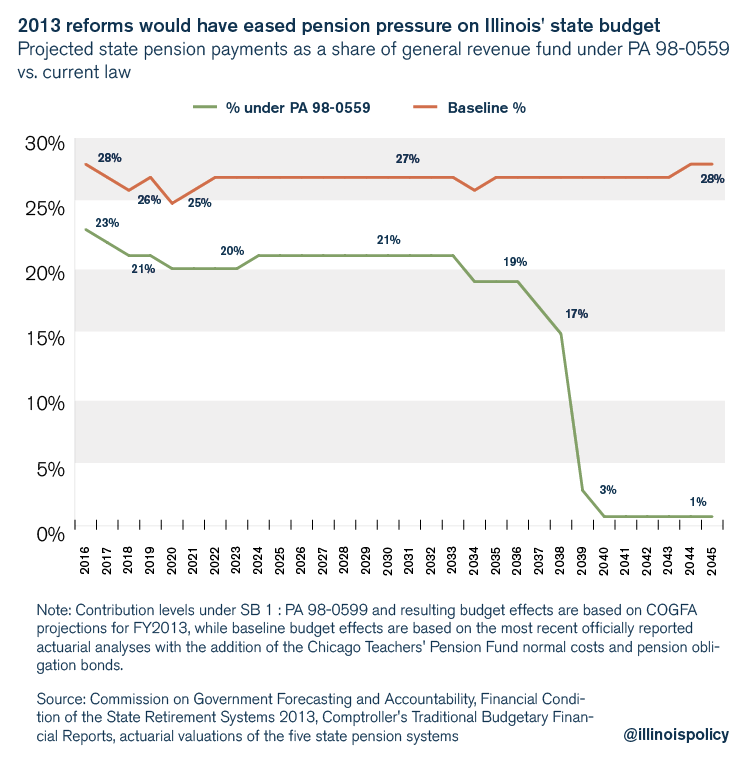

Lawmakers should look to the reform effort in 2013, encapsulated in Senate Bill 1, for examples of benefit changes that could solve the state’s pension problem.21 The plan was passed through a supermajority Democrat-controlled General Assembly and signed by Democratic former Gov. Pat Quinn five years ago.

Under that reform bill, no current worker would have received less than she is currently promised, and no retiree would have seen her monthly check decrease. The reform concepts – modifying cost-of-living adjustments, increasing retirement ages for younger workers and capping the maximum pensionable salary – would have only affected the rate of future benefit accruals.

Several states already create a legal distinction wherein earned pension benefits are protected but future accruals remain open to change, including Louisiana, Hawaii and Michigan.

The 2013 reforms were imperfect mostly because they did not create a sustainable and affordable retirement system in which new hires would be required to participate under new rules. The bill had other technical flaws as well. Still, SB 1 would have had dramatic and positive effects on the state budget.

If the Illinois Supreme Court had not struck down SB 1, the state would have saved between $1.1 billion and $1.4 billion per year from fiscal year 2016 to 2019, the four budget years under former Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner. Savings of this magnitude could have prevented the budget impasse between Rauner and Madigan, thereby also preventing the resulting automatic cuts to higher education and social services.

A new pension contribution schedule should be built on the following concepts, which are similar to those in SB 1:

- Increasing the retirement age for younger workers, to bring them in line with private-sector retirement ages

- Capping maximum pensionable salaries to limit excessive pensions

- Replacing permanent compounding benefit increases with true cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs

- Implementing COLA holidays to allow inflation to catch up to past benefit increases

- Ensuring government worker retirements are predictable and sustainable going forward. To achieve that, all newly hired employees should be automatically enrolled in defined contribution retirement plans, similar to what’s overwhelmingly used in the private sector and what is already offered to state university employees.

These changes would apply to existing workers and retirees, but only to future benefits. The state already implemented a Tier 2 pension system for workers hired after Jan. 1, 2011. Tier 2 pensioners have more reasonable retirement ages, higher employee contributions, a cap on maximum pensionable salary and a COLA indexed to inflation.22

The state should move to treat everyone equally, putting all current plan participants on the same benefits package.

With certain changes, such as requiring COLA holidays for those who have gained the most from years of benefit increases in excess of inflation, a contribution schedule based on these reforms could save more than $1.1 billion during each of the next four years.

According to actuarial projections at the time, savings would fall below $1 billion for the next four fiscal years, but then rise again and continue to rise thereafter. The temporary decrease in savings still leaves the state saving between $715 million and $981 million for those years. The cause of the decrease is that SB 1 also increased the funding target to 100 percent from 90 percent and used an actuarial funding method that is in line with best practices set by the Actuarial Standards Board, which publishes uniform Actuarial Standards of Practice.23

The Illinois state actuary, part of the Office of the Auditor General, has consistently recommended adopting a funding plan in line with generally accepted actuarial principles. Specifically, the recommendation is for the state to move toward a repayment schedule that targets 100 percent funding during a period of no more than 20 years.24 According to the state actuary, current funding practices violate Actuarial Standard of Practice No. 4, “Measuring Pension Obligations and Determining Pension Plan Costs or Contributions.”25

SB 1 would have fixed that deficiency.

Between fiscal years 2016 and 2045, SB 1 would have reduced total contributions by $145 billion without taking away a penny from any retired worker or reducing the annuity of any current worker.

Aligning responsibility with accountability

A second way Illinois can see immediate pension savings would be to realign the cost of paying for “normal costs” – the pension cost of an additional year of work – so that the one responsible for setting benefit levels is accountable for paying the bill.

Under the status quo, K-12 and state university administrators negotiate salary and health benefits, which form the basis for pension payments and retiree health costs, but the state pays the bill. That creates a misalignment between responsibility and accountability, reducing pressure to keep compensation affordable for taxpayers.

In other words, realigning future pension costs for schools and universities would save money for the state and encourage administrators to control the costs of pensions in the long run through more responsible collective bargaining.

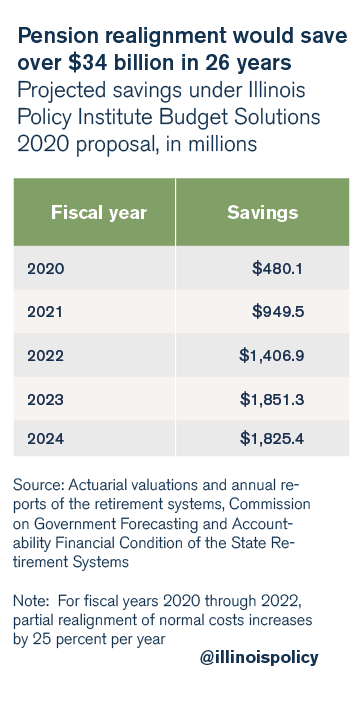

Rauner proposed this idea in each of his budget addresses.26 Madigan also supported the idea in 2012,27 and said the change was inevitable as recently as 2013.28 If phased in over four years to allow schools and universities time to adjust, pension savings would be $480 million in the first year and rise to nearly $2 billion by the fourth year.

Realigning responsibility to pay for pension benefits in this way would only increase each district’s payroll costs by about 2.5 percent per year, on average.29 The state would remain responsible for making payments on the unfunded portion of the pension liability so schools would be paying only the new annual cost of pensions.

Still, school districts should be empowered to balance their own budgets more easily through relief from unfunded mandates,30 school district consolidation and some local sharing of recreational marijuana revenues as has been done in Colorado.31

Pritzker has also endorsed a gambling expansion in the state. The Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or COGFA, estimates that more gaming could generate between $75 million and $200 million in additional revenue.32 Nearly all of that new revenue would go to local sources, with only $12 million going to the state, according to COGFA testimony about a gambling expansion bill in Spring 2018.33

Finally, schools can find savings to help absorb the new cost by ending the practice of teacher pension pick-ups. An analysis of the most recent Teacher Salary Study from the Illinois State Board of Education, or ISBE, shows that 514 of 860 school districts that responded to ISBE’s most recent teacher salary survey, or 59 percent, picked up some or all of the employee share of pension contributions.34 In 21 Illinois school districts, teachers contribute nothing at all to their own retirement. Taxpayers simply cannot afford to offer this perk any longer.

Additional savings of $238 million in Year 1 can be found by asking schools and universities to pay the cost of another special perk for public education employees: retiree health care for life. This figure is obtained by taking the $234 million of savings proposed in Rauner’s fiscal year 2019 budget and assuming 2 percent inflation.35

An analysis from Mercer, a human resources consulting firm, found in 2011 that offering retiree health care for life is rare in both the public and private sectors – with fewer than 25 percent of large employers offering the perk and very few small employers – and that the prevalence of the perk is declining.36

As with pension benefits, schools and universities should be accountable for costs they create if they want to provide retiree health care for life.

Investing in classrooms over bureaucracy: $2.9 billion over 5 years

Pritzker has made clear his intention to spend more money on K-12 education.37

Trying to improve educational outcomes and the education system in Illinois is a valuable goal. Getting more money into classrooms is part of the answer for achieving this goal. Money spent on instruction – investing in high-quality teachers and classroom supplies – could enable students to learn more and be better prepared for college and careers.

However, there are better ways to put more money into classrooms than spending inordinate amounts of new money on K-12 education in absolute terms. Redirecting a significant amount of education spending to classrooms from administration is one of the chief ways Illinois could help children and support teachers more directly. By combining school district consolidation with technical changes to the state’s new funding formula, the state could make significant additional investments in classrooms by growing state spending at the rate of inflation, rather than the $350 million envisioned under current law.38

In 2017, Rauner signed into law a new funding formula for state spending on K-12 education.39 The formula is intended to make the distribution of state education dollars to school districts more equitable, with most new money going to districts with high rates of poverty, low local property wealth and high numbers of at-risk students.

The formula works by first assigning a unique “adequacy target” to each school district. The adequacy target is the amount of money the formula envisions is needed to provide a quality education given the characteristics of the school district. Factors include the percentage of students in a district who are poor or learning disabled, because such students often require additional attention and resources. Next, the formula assigns each school a “local capacity target” value, which is supposed to represent the amount of money available from local revenue sources given the property wealth of the district.40

Finally, while no district gets less than it did prior to the bill’s passage, each school is assigned to a funding “tier” from 1 to 4. Tier 1 schools get the vast majority of new education dollars, no district gets less than they got prior to the bill’s passage, and Tier 4 districts get the least.41 An analysis of the first year of data made available by ISBE shows that 37 percent of Illinois districts were classified as Tier 1, 41 percent Tier 2, 6 percent Tier 3, and 17 percent Tier 4.42

The formula also envisions increasing total K-12 education spending by $350 million per year.43

Illinois’ administrative waste in K-12 education

While the goal of increased education spending is good, pouring more money into the state’s education system as it exists today will mean a poor return on investment for students and taxpayers alike. Instead, Pritzker should support reforms such as school district consolidation – not consolidating any schools themselves, but the top layer of administrative overhead at the district level – in order to reduce the amount of bureaucratic bloat and waste in education spending.

If coupled with meaningful school district consolidation, lawmakers can make significant additional investments in classrooms, students and teachers without increasing the burden on the state budget or taxpayers. By growing K-12 spending at 2 percent per year, the long-run expected rate of inflation, instead of the $350 million envisioned under current law, Pritzker can save $2.9 billion in five years while improving educational outcomes for students and increasing teacher pay.

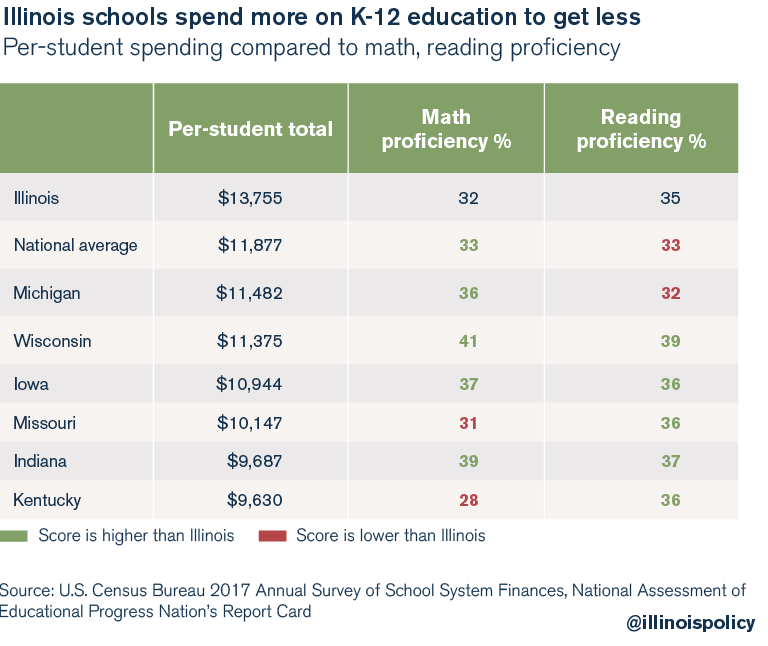

Illinois currently spends more per student than any of its neighboring states or the national average, but achieves outcomes that are middling at best and well below what neighboring states achieve with less spending per student.

If Illinois reduced its spending to the estimated national average of $11,989 per student in fiscal year 2017, it would have spent roughly $8.5 billion less.44 Meanwhile, neighboring states are spending between $2,380 and $4,125 less per pupil to achieve overall better results for their students.

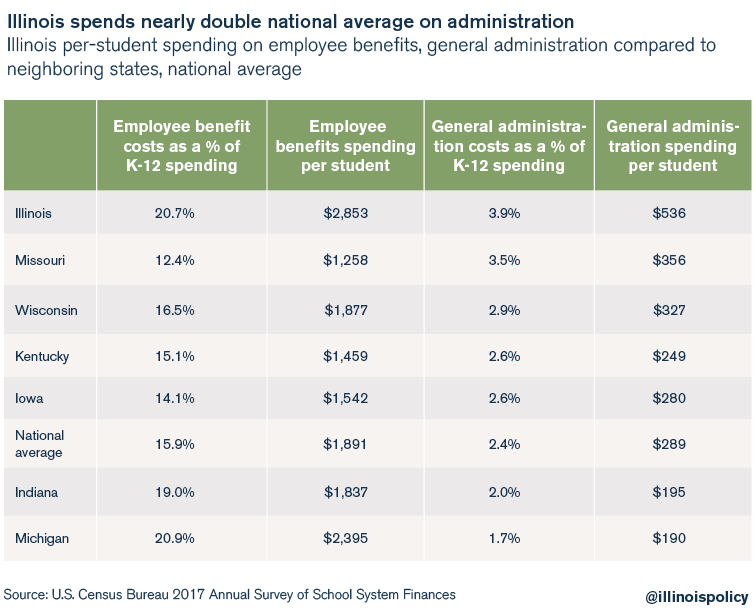

A major reason for this disconnect between per-student spending and educational outcomes is that Illinois spends too much on general administration and employee benefits, much of which goes to high-salary administrators.

According to U.S. Census Bureau definitions,45 “general administration” costs are those for the board of education and executive administration, meaning superintendents along with their staffs and expenses. This spending category is distinct from “school administration,” or spending for the principal and administrative staff within the school. “Employee benefit” expenditures are for money spent on compensation other than salaries or wages, such as retirement coverage and health insurance costs.

Illinois spends too much money on school district bureaucracy, which rarely interacts with students and parents, and which performs duties that could be consolidated or picked up by teachers and administrators within the schools themselves. Much of this bureaucracy would be unnecessary but for the numerous unfunded mandates placed on schools, which were mentioned earlier as an opportunity for local schools to save money.

In fact, Illinois serves far fewer students per school district compared to other large states – those with student populations greater than 1 million – as well as compared to the national average.46

Studies taking into account multiple variables show better outcomes from leaner top-down administration, measured by the number of students served per school district, likely because it means more money is making it to the classroom.47

Illinois has far too many small school districts serving too few students. The state also has too many separate high school and elementary districts, considering that unit districts are the most efficient as measured by per-student spending.

To solve this problem, Pritzker should lobby for a school district consolidation commission. The commission should be given a goal, such as consolidating districts in a way to reach the same number of students served per district on average as Virginia or as the national average. The goal would be to reach a statewide average, not a mandate on each district, and local educators and parents should have their voices heard by the commission.

Then, once the commission has finalized recommendations, those recommendations should go directly to voters for approval on a ballot referendum.

The exact savings from school district consolidation will depend on how aggressive a target is set for the commission. If the target is 210 districts per the Virginia model, the elimination of 642 districts would mean a 75 percent reduction in administrative overhead.

An analysis of ISBE’s Educator Employment Information database for 2017 shows that the state has 1,063 administrators with the word “superintendent” in their title – a category including assistant regional superintendents, assistant/associate district superintendents, district superintendents, and regional superintendents. There are another 1,007 K-12 education employees with the title “general administrator” or “general supervisor.”48

Reporting of salary and especially benefits for these individuals is incomplete in the database, but ISBE data show the total cost of employing these general administrators is at least $277.4 million annually given available data. A 75 percent reduction in these costs would mean $208 million more in education dollars for classrooms annually, as a rough estimate of potential savings resulting from reducing administrative bloat.49 Final savings would likely be even higher as schools could sell excess property from former district buildings as well as collect property taxes on those now private sector lots.

It is worth noting that Democratic former Gov. Pat Quinn supported school district consolidation.50

Promoting equity in the funding formula

Along with pushing for significant school district consolidation, Pritzker should fix certain technical flaws of the education funding formula that run contrary to its purpose of sending more education dollars to the schools most in need.

Two reforms in particular are required.

First, the education formula adds $742 of “central office investments” per K-12 student to each school district’s adequacy target.51 This incentivizes more spending on administration, regardless of need, and discourages local districts from finding ways to be more efficient by spending less on administration per student.

In 2017, there were over 9,000 school administrators in Illinois who made $100,000 or more per year; each of these administrators is expected to receive $3 million or more during the course of her retirement, due to generous taxpayer-funded pensions.52

The growth of these administrative positions has far exceeded the growth in the student population. From 1992 to 2015, nonteaching and administrative staff in Illinois grew by 49 percent; this was almost 4.5 times as fast as the growth in the K-12 student body population, which grew by only 11 percent during that same period. If the growth in nonteaching and administrative staff had been the same as student growth, Illinois would have saved $750 million annually from 1992 to 2009. Taxpayers would have needed to support 33,000 fewer such employees and their pensions.53

Reducing the number of school districts to a level more closely resembling similarly sized states would help reduce the number of these expensive administrative positions, but schools also should not be awarded additional taxpayer dollars that encourage adding unnecessary administrative positions.

Second, Pritzker should ask the General Assembly to delete a “trigger provision” that was added to the funding formula. The provision states: “If at any time the responsibility for funding the employer normal cost of teacher pensions is assigned to school districts,” then that amount shall be added to the calculation of the district’s adequacy target.54

This provision undermines the purpose of the funding formula by potentially prioritizing education dollars for the wealthiest school districts, which tend to have the highest salaries and therefore the highest pension benefits.55

In other words, if the state ever properly aligns accountability and responsibility to pay for pensions – without removing the trigger provision – wealthy districts would be moved up the funding tier as the normal cost of their pensions inflated their adequacy target.

By making these technical fixes in the state’s funding formula and pursuing significant school district consolidation, Pritzker can increase spending on K-12 education by less than current law assumes while still improving education outcomes. Sending proportionally more money to classrooms would increase the value obtained for students and teachers more than merely dumping money into the existing bureaucracy-heavy system.

Asking government unions to play fair at the bargaining table: $4.2 billion over 5 years

While Pritzker received the endorsement of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees during his campaign for governor,56 he nevertheless must ask the union for changes to make the next contract more affordable than the last one. This is essential to balance the budget and put Illinois on a path toward long-term fiscal health.

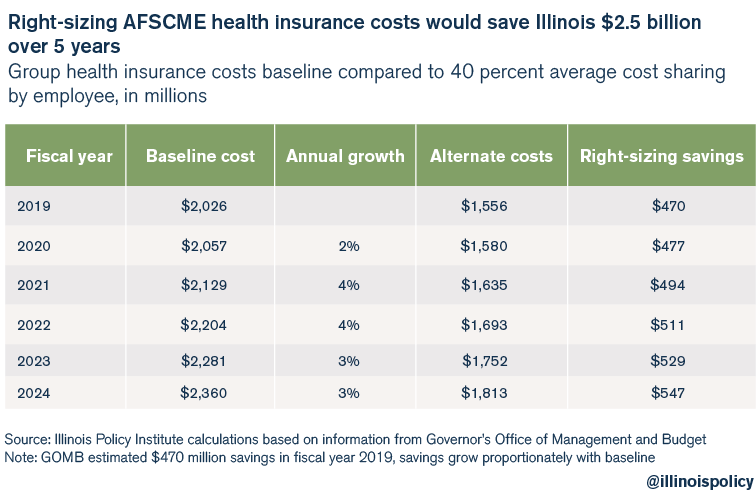

Right-sizing group health insurance costs

Illinois state workers receive platinum-level health insurance, according to classifications from the state’s health care exchange,57 at relatively little cost to themselves.

Under benefits provided in the now-expired contract with the state, as of 2016, the average AFSCME worker paid just 23 percent of their total annual health care costs while taxpayers subsidized the remaining 77 percent. As of 2015, when the state contract expired and under which the state still operates until a new contract is signed, state workers on average paid $2,904 in annual premiums and $1,548 for out-of-pocket expenses such as deductibles and co-pays, while the state paid $14,880 per worker.58

AFSCME workers paid just 16 percent of the annual premium costs as of 2016,59 while private sector employees with employer-sponsored health benefits pay on average 31 percent of premium costs for family plans, not even including out-of-pocket costs, according to a 2017 study by the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.60 Workers in private sector firms with many low-wage workers pay even more, an average of 37 percent of their family coverage premiums.61

A previously proposed plan would have right-sized group employee health insurance costs by bringing them more in line with the private sector.62 The plan would have created three tiers of insurance: one with higher premiums, one with higher out-of-pocket costs and a mixed plan. Each of the plans would have increased the employee share to 40 percent on average.63

If Pritzker were to revive this offer to right-size health insurance costs for state workers, he could save taxpayers $477 million in Year 1 and $2.5 billion during the course of five years.

One option to achieve these savings would be to simply negotiate them with AFSCME, but the General Assembly also has the power to implement the change.

A bill proposed last year, Senate Bill 2680, would have removed health care coverage from the subjects of collective bargaining as long as average employee costs remained below 40 percent annually.64 The bill died in the Senate, but could be revived in the upcoming legislative session to make sure health care costs are controlled regardless of who occupies the governor’s office.65

Limiting automatic raises for some of the nation’s highest-paid government workers

Illinois state workers are now the second-highest paid in the nation, adjusting for cost of living, and their wages have risen 43 percent from 2005 to 2015, compared to just 11 percent for private sector Illinoisans, according to Wirepoints.66 A study by The Pew Charitable Trusts in 2018 found that overall, personal income growth in the Land of Lincoln is tied for second worst in the nation since the Great Recession.67

A major reason for this poor private-sector income growth is income tax increases in Illinois in 2011 and 2017,68 which have been used to prop up the state’s overspending, including on public employee compensation.

Just two years ago, in 2016, Illinois’ state workers were the highest paid in the nation, adjusted for cost of living.69 It’s possible that would still be the case if not for a contract dispute between Rauner and AFSCME.70

As a result of that dispute, AFSCME has not been receiving automatic raises, or “step increases,” since their last contract expired on June 30, 2015.71 Unfortunately for taxpayers, the union has been able to use legal mechanisms to delay the implementation of a new contract for Rauner’s entire term. If Pritzker gives in to the union’s entire list of demands it presented to Rauner’s team, it would cost taxpayers an additional $3 billion over the course of the contract.72

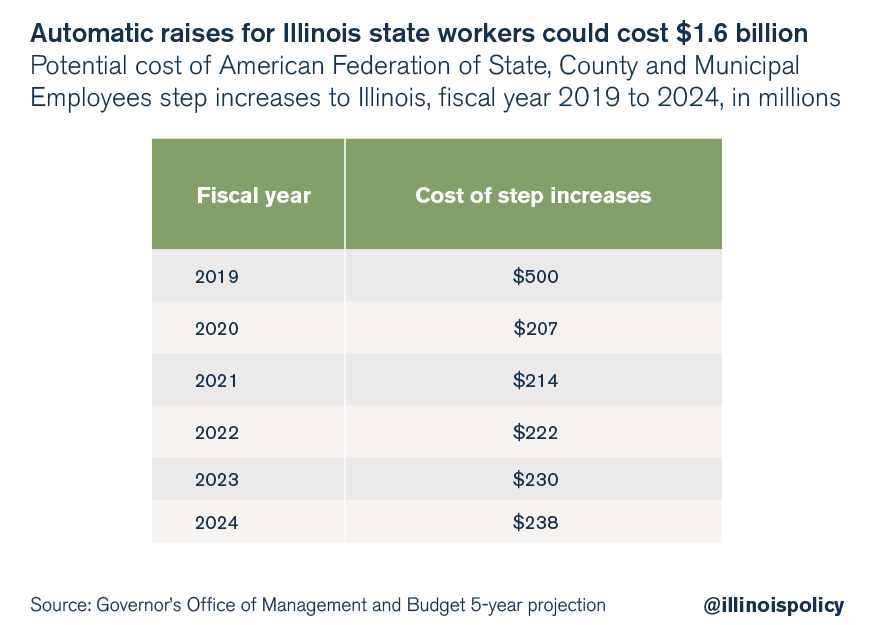

Just one aspect of their contract demands, the resumption of automatic pay raises, would cost $1.6 billion over the next five years.73

The cost is highest in the first year, when workers could be paid for past step increases despite the lack of a contract under Rauner.

For one of his first official acts in office, Pritzker announced Jan. 15 that he will grant automatic pay raises – also known as “step increases” – to Illinois state workers for the second half of fiscal year 2019. His move will likely cost state taxpayers around $100 million based on previous GOMB projections.74 However, the move is prospective only because it does not address the dispute over potential “backpay” during Rauner’s term as governor. Pritzker can still achieve significant savings by continuing to fight the backpay issue and by negotiating a new contract that does not include automatic raises.75

The costs of automatic pay raises and Cadillac health insurance do not even include other benefits demanded by AFSCME, such as overtime starting at 37.5 hours worked weekly.76

Although the union endorsed Pritzker, Illinois’ new governor must ask AFSCME to play fairly at the bargaining table and not revive automatic raises. Instead, Pritzker should offer AFSCME a benefit that is affordable and encourages hard work, such as merit pay and incentive bonuses.77

Democratic former Gov. Pat Quinn also supported changes to control the state’s group health insurance costs as well as a wage freeze.78

Pritzker can deliver a more reasonable and cost-effective contract for taxpayers by starting with these two commonsense savings ideas, without even going after other perks such as accelerated overtime pay and time off for union work.79

Budget process reform to keep Illinois on the right track

Aside from the dollars and cents of budget making, Illinois should also look to reform its broken budget process that has contributed to such bad budgeting outcomes for taxpayers.80 This will ensure spending restraint is maintained in the long term and will prevent problems from recurring in coming decades.

It is easy to blame elected leaders for the state’s fiscal health, and that blame is not misplaced. Historically, Illinois lawmakers have shown a policy preference for overspending and fiscal irresponsibility. However, there is a less-well-known culprit that is equally important and potentially more pernicious: the budget process itself.

Expert literature shows the budget process is an important contributor to budget substance.81 States with different laws and procedures around budget making have been able to enforce fiscal discipline on their lawmakers and avoid many of the issues plaguing Illinois.82 These problems include the worst-funded public pension system in the nation, billions of dollars of unpaid bills, the nation’s lowest municipal bond rating, a tax burden that is crippling the state economy and a years-long outmigration crisis.

The following aspects of Illinois’ budget system are particularly problematic:

1. Inherently unreliable revenue estimates, which are a source of political conflict and undermine the starting point of budget negotiations.83

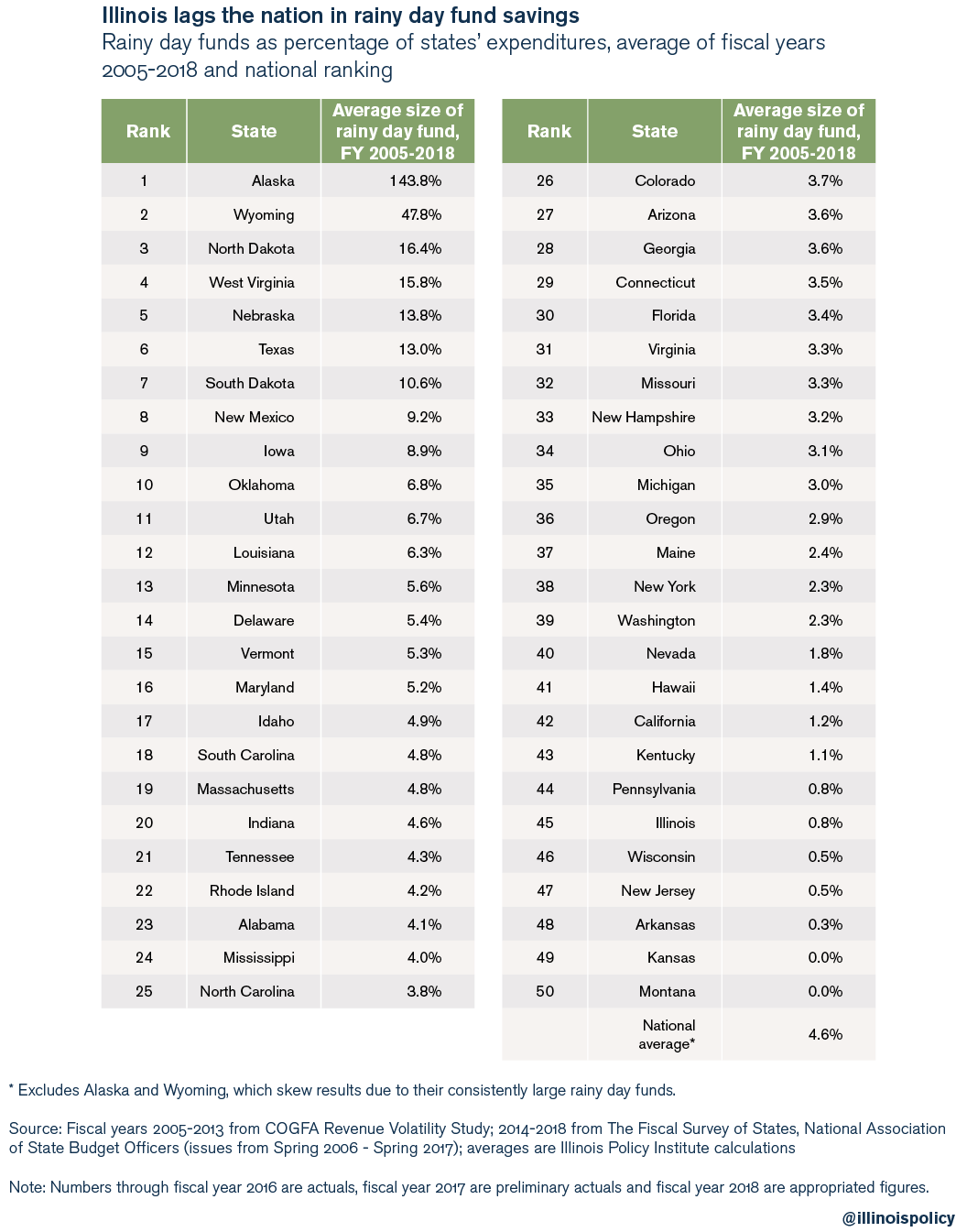

2. Poor savings habits and the lack of a sufficient rainy day fund make Illinois vulnerable to fiscal shocks.84

3. Reliance on short-term borrowing and fund sweeps for annual operating needs undermines the long-term sustainability of government spending.85

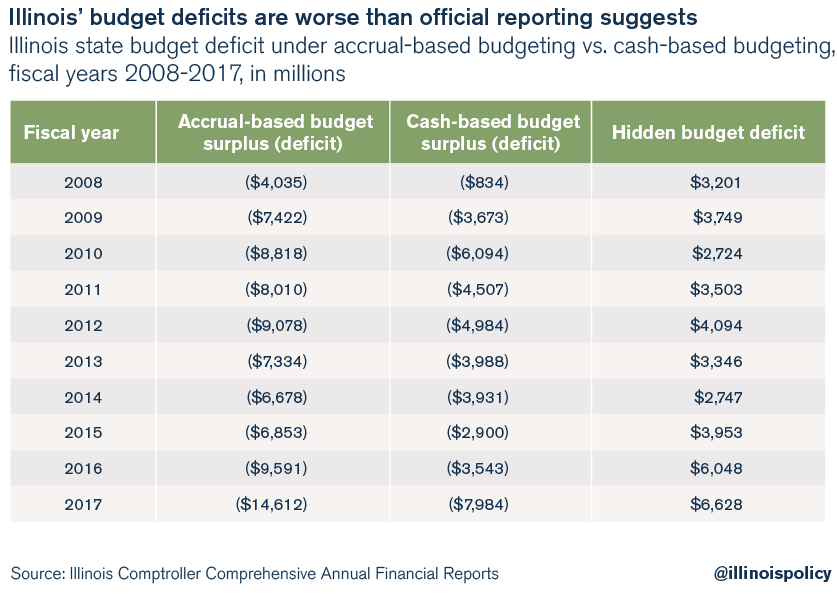

4. Bad accounting practices for the budget process deny taxpayers transparency and lawmakers the information they need to make good decisions. By using cash-based accounting, rather than full accruals or generally accepted accounting principles, or GAAP, accounting, the state is able to keep spending off the books until a bill is actually paid, rather than when a cost is incurred.86

These issues are interconnected and mutually reinforcing.

By demanding change in the budget process, taxpayers can put Illinois on a path to fiscal discipline for decades to come. Lawmakers should immediately enact the following reforms to fix the four key issues with the budget process:

1. Replace faulty revenue estimates with a reliable starting point:

a. Adopt a spending cap tying annual growth in spending to a 10-year average of economic growth. This would improve the accuracy of budget planning and reduce political conflict in negotiations, rather than relying on imperfect revenue estimates to plan spending. The five-year plan presented above would spend within the means imposed by such a cap.

b. Revenue estimates should still be required and should statutorily require automatic averaging between COGFA and GOMB estimates, rather than relying on the General Assembly to pass a resolution.

2. To address the paltry rainy day fund and volatile taxes, surpluses resulting from the spending cap should be used to do the following:

a. Pay down the backlog of unpaid bills.

b. Rebuild the Budget Stabilization Fund to at least 5 percent of annual expenditures. Simultaneously, lawmakers should strengthen restrictions on when funds can be withdrawn.

c. Cut income tax rates to provide tax relief and improve the predictability of Illinois’ tax portfolio.87

3. Avoid one-time revenue infusions by limiting lawmakers’ ability to rely on spending gimmicks, without creating a patchwork of constitutional carveouts:

a. Redefine revenue to exclude debt, refinancing and fund sweeps.

b. Avoid issuing bonds to pay for yearly operations or pension costs.

4. End bad accounting practices that hide the true size of deficits:

a. Adopt accruals-based budgeting so that budget balance is defined by including the present value of assets and the long-term cost of liabilities.

b. Strengthen the balanced budget provision of the Illinois Constitution to require end-of-year balance, rather than just prospective balance. Expert literature shows that this is the most effective spending constraint among state budget processes.88

If Pritzker and the General Assembly adopted these comprehensive solutions, they could fix Illinois’ broken budget process and put the state on a path to a more stable, financially responsible and secure future.

Conclusion

Pritzker has an opportunity to fix Illinois’ finances, eliminate its debt and deliver tax relief to overburdened taxpayers. Doing so requires only political courage and a realistic assessment of the status quo.

If one examines the math of Illinois’ budget, the path to reform becomes clear. Spending on pension benefits and government worker health insurance is crowding out other priorities. Money spent on K-12 education is being siphoned away from the classroom to a top-heavy bureaucracy. And demands by AFSCME would make the state’s contract with its employees unaffordable.

Fortunately, solutions exist to each of these problems. The cost drivers of Illinois’ debt and deficits can be reined in through fair and thoughtful reforms that warrant bipartisan support.

Taxpayers in Illinois are overburdened. They deserve certainty and relief. It’s up to Pritzker and the General Assembly to face the crisis and deliver on the opportunities.

Endnotes

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Illinois Economic and Fiscal Policy Report,” November 15, 2018.

- Eileen Norcross and Olivia Gonzales, Ranking the States by Fiscal Condition 2018, (Mercatus Center at George Mason University, October 9, 2018), https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/norcross-fiscal-rankings-2018-mercatus-research-v1.pdf

- John O’Connor and Sophia Tareen, “Illinois Approves Spending Plan, Ending Nation’s Longest Budget Stalemate,” PBS News Hour, July 6, 2017.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois Has the Lowest Credit Rating on Record for a US State,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 1, 2017.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Bonds Once Again Rated Just Above Junk,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 10, 2018

- Adam Schuster, “Moody’s: Illinois Pension Debt-to-Revenue Ratio Hits All-Time High for Any State,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 31, 2018.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “Special Pension Briefing,” November 2018.

- Matthew Frankel, “How Does the Average American Spend their Paycheck? See How You Compare,” USA Today, May 8, 2018.

- Illinois Policy Institute analysis of: National Association of State Retirement Administrators, “State and Local Government Spending on Public Employee Retirement Systems,” March 2018.

- Ibid, excludes one-time cash infusion from Alaska.

- Michael Cembalest, “The ARC and the Covenants 4.0,” J.P. Morgan Private Bank, October 9, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Illinois Economic and Fiscal Policy Report,” November 15, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Associated Press, “Madigan Supports Pritzker Efforts on Marijuana, Income Tax,” November 13, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Marijuana Policy Project, “Illinois General Assembly to Consider Ending Marijuana Prohibition, Regulating and Taxing Marijuana for Adult Use,” March 22, 2017, https://www.mpp.org/news/press/illinois-general-assembly-consider-ending-marijuana-prohibition-regulating-taxing-marijua- na-adult-use/.

- GOMB, 5-year projections.

- Adam Schuster, “Tax hikes vs. reform: Why Illinois Must Amend its Constitution to Fix the Pension Crisis,” Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2018.

- Constitution of the State of Illinois, Article XIV, Section 2.

- Illinois Public Act 098-0599.

- 40 ILCS 5/15-108.2.

- Actuarial Standards Board, Actuarial Standards of Practice.

- Office of the Auditor General, “State Actuary’s Report,” State of Illinois, December 2017.

- Ibid, p. 93 & p. 99. Specifies that it violates ASOP No. 4 Section 3.14.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Proposed Operating Budget,” Fiscal Years 2016 through 2019.

- Greg Bishop, “Lawmakers Debate Governor’s Pension Cost Shift Proposal,” Illinois News Network, May 10, 2018.

- Doug T. Graham, “Madigan: Putting Pension Costs on Schools ‘Going to Happen’,” Daily Herald, May 10, 2013.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois’ Regressive Pension Funding Scheme: Wealthiest School Districts Benefit Most,” Wirepoints, March 9, 2018.

- Local Government Consolidation and Unfunded Mandates Task Force, “Final Report,” State of Illinois, December 17, 2015.

- Colorado Department of Education, “Marijuana Tax Revenue and Education,” June 2018.

- Ted Slowik, “Lawmakers Weigh Concerns About Potential Gaming Expansion that Could Land Casino in South Suburbs,” Daily Southtown, Au- gust 22, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on ISBE 2017-2018 Teacher Salary Study.

- Adam Schuster, “Civic Federation Calls For Tax Hikes, Opposes Sensible Reform In Budget Criticism,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 17, 2018

- Mercer, “Retiree Healthcare Contributions,” prepared for the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, May 17, 2011.

- See e.g., Daily Herald, “JB Pritzker: Candidate Profile,” February 13, 2018; Adam Schuster, Orphe Divounguy, and Bryce Hill, “Pritzker Price Tag: Candidate’s Spending Promises Require Doubling State Income Tax,” Illinois Policy Institute, Fall 2018.

- Illinois Public Act 100-0465.

- Ibid.

- Illinois State Board of Education, “An Overview of The Evidence-Based Funding Formula,” Fall 2017.

- Ibid.

- Illinois State Board of Education, “Illinois Report Card,” 2018.

- P.A. 100-0465.

- National Education Association, “Rankings of the States 2016 and Estimates of School Statistics 2017,” May 2017 and ISBE 2017 Annual Report. Savings estimated by multiplying the difference in estimated U.S. average per pupil expenditure (NEA, $11,984) and Illinois FY17 actual per student expenditure (ISBE, $16,179) by the actual fall 2017 Illinois enrollment (2,028,162). [($16,179-$11,984) X 2,028,162]

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Annual Survey of School System Finances,” last revised May 17, 2018.

- National Education Association, “Rankings of the States 2017 and Estimates of School Statistics 2018,” April 2018.

- See e.g., Christopher R. Berry and Martin R. West, 2008, “Growing Pains: the School District Consolidation Movement and Student Outcomes,” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 26(1): 1-29; Ulrich Boser, “Size Matters: A Look At School-District Consolidation,” Center for American Progress, August 2013; Johnathan Butcher, “Arizona School Districts Can Eliminate Wasteful Spending to Increase Teacher Pay,” Gold- water Institute, September 12, 2018; Tatia Lynn Prieto, 2016, “An Analysis of Administrative Spending Across Education Organizational Forms,” University of North Carolina at Charlotte, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on Illinois State Board of Education, “Educator Employment Information,” 2016-2017 data set.

- Ibid.

- Ulrich Boser, “Size Matters: A Look At School-District Consolidation,” Center for American Progress, August 2013, p. 1.

- Illinois Public Act 100-0465.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Education Finance Solutions: Making Illinois’ System Fairer Through Pension Reform, Consolidation and Accountability To Parents and Students,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2017.

- Ben Scafidi, “Back to the Staffing Surge,” edChoice, May 8, 2017.

- Illinois Public Act 100-0465.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois’ Regressive Pension Funding Scheme: Wealthiest School Districts Benefit Most,” Wirepoints, March 9, 2018.

- Greg Hinz, “AFSCME Endorses J.B. Pritzker,” Crain’s Chicago Business, April 27, 2018.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Proposed Operating Budget,” State of Illinois, Fiscal Year 2019, p. 47.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “AFSCME Health Benefits, Wages Out Of Sync with what Illinois Taxpayers Can Afford,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2016.

- Ibid.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, “2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey,” September 19, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Proposed Operating Budget,” State of Illinois, Fiscal Year 2019.

- Dabrowski and Klingner, “AFSCME Health Benefits, Wages Out Of Sync.”

- Senate Bill 2680, 100th Illinois General Assembly.

- Mailee Smith, “Bill to Rein in State Health Care Costs Killed in the Senate,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 27, 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Six Facts Pritzker Can’t Ignore When Negotiating AFSCME’s Contract,” Wirepoints, November 27, 2018.

- Vincent Caruso, “Illinois’ Income Growth Second-Worst in the Nation,” Illinois Policy Institute, September 14, 2018, citing “States’ Economic Expansion Picks Up After a Lull,” Pew Charitable Trusts, September 10, 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy and Bryce Hill, “Jobs Data: After 2017 Income Tax Hike, Illinois Slows While Nation Grows,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 2, 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois State Workers Highest Paid in the Nation,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2016.

- Mailee Smith, “AFSCME’s List of Demands,” Illinois Policy Institute, January 27, 2017.

- Austin Berg, “How to Make an Extra $3 Billion, the Illinois Way,” Illinois Policy Institute, October 25, 2018.

- Ibid.

- GOMB 5-year projections.

- Adam Schuster, “Pritzker gives $100 million in Pay Raises to Some of Nation’s Highest Paid State Workers,” Illinois Policy Institute, January 15, 2019.

- Pritzker’s decision to provide automatic raises for half of fiscal year 2019 does not materially affect the projections in budget solutions. The estimated cost of $100 million is less than the average error in revenue forecasts. Additionally, the largest savings can be found in continuing to litigate the issue of step-increase “backpay” and negotiating a new AFSCME contract which does not contain step increases.

- Mailee Smith, “AFSCME’s List of Demands.”

- See Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Illinois State Workers Highest Paid in the Nation”; Mailee Smith, “AFSCME Leaders Rejected Offer of Bereavement Leave, Performance Bonuses,” October 27, 2016.

- Doug Finke, “Governor Quinn Terminates AFSCME Contract,” State Journal-Register, November 21, 2012.

- Mailee Smith, “AFSCME: The 800-pound Gorilla at the Negotiating Table,” Illinois Policy Institute.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Budgeting Basics: How Illinois’ Broken Budget Process Hurts Taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2018.

- See, e.g., Henning Bohn and Robert P. Inman, “Balanced-Budget Rules and Public Deficits: Evidence from the U.S. States,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 45 (1996): 13-76; Gary A. Wagner and Erick M. Elder, “The Role of Budget Stabilization Funds in Smoothing Government Expenditures over the Business Cycle,” Public Finance Review, 33(4) (2005); Antonio Fatás and Ilian Mihov, “The Macroeconomic Ef- fects Of Fiscal Rules In the US States,” Journal of Public Economics, 90 (1-2) (2004): 101-117; Fred Thompson and Bruce Gates, 2007, “Betting on the Future with a Cloudy Crystal Ball: Revenue Forecasting, Financial Theory, and Budgets – An Expanded Treatment,” Public Administration Review, 67(5), October 2007; Leslie Mattoon and McGranahan, 2012, “Revenue Cyclicality and Changes in Income and Policy,” Public Budgeting and Finance 32(4), December 2012, 95-119; Donald J. Boyd and Lucy Dadayan, “State Tax Revenue Forecasting Accuracy,” Rockefeller Institute of Government, September 2014.

- Richard Dye, David Merriman, and Andrew Crosby, “Improving Budgetary Practices in Illinois,” The Fiscal Futures Project, December 7, 2015; Dave Murtaza, “Three Ways to Improve Illinois’ Budget Process,” Better Government Association, February 15, 2018.

- For example, the legislative and executive branches may produce competing estimates that serve their unique political ends. These competing estimates can become a source of conflict before budget negotiations ever begin. See, e.g., William R. Voorhees, “More Is Better: Consensual Fore- casting and State Revenue Forecast Error,” International Journal of Public Administration, 27 (8-9) (2004): 651-671.

- Rainy day fund savings are the primary way state governments should deal with economic downturns. See, e.g., Gary C. Cornia and Ray D. Nelson, “Rainy Day Funds and Value at Risk,” Conference on State Fiscal Crises: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions, Urban Institute, Brookings Institution, Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management and Institute for Policy Research, April 3, 2003, published in State Tax Notes, August 25, 2003.

- See, e.g., Volcker Alliance, “Truth and Integrity in State Budgeting,” 2017.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Accounting Hides True Size of Illinois’ Budget Deficits,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 19, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Budgeting Basics.”

- See, e.g., Daniel L. Smith and Yilin Hou, “Balanced Budget Requirements and State Spending: A Long-Panel Study,” Public Budgeting and Fi- nance 33(2), Summer 2013, 1-18.